Enab Baladi Investigation Team

Assyrians’ roots date back to the Assyrian Empire that ruled Mesopotamia around 7000 years ago before the advent of Christianity.

Assyrians are considered as one of the oldest populations which converted to Christianity since the first century AD and contributed to the spread of this religion in the areas of Central Asia, India and China, according to some historical references.

Some historians note that the Assyrian Empire collapsed around 600 years BC. Over the past centuries the remaining members of the empire have been subjected to several massacres, and have struggled to preserve their cultural heritage and identity, relying on the Church which helped preserve their language and boost their sustainability.

Assyrians live today as minorities in some Syrian and Iraqi areas, along with the Arabs and Kurds, and express themselves through some small political parties and cultural associations, which struggle to get the Assyrians out of a conflict in a region seething with war.

Religious and Ethnic Minority Resisting the Flood of War

In the 1920s, thousands of Assyrians escaped prosecution and fled from south-eastern Turkey to Upper Mesopotamia to seek refuge on the outskirts of their demolished villages, and close to the homeland of their ancient civilization.

The French opened the north-eastern gate of Syria to the Syriac Assyrians and gave them lands to live and settle in. Thus, they become an ethnic minority and an addition to few other thousands of Syriacs who lived with the inhabitants of some Syrian areas.

Informal sources estimate the number of Assyrians in Syria to be around 30,000 before the Syrian revolution out of about one and a half million Christians. This number is likely to have declined somewhat after the war, due to migrations and as a result of the several attacks of ISIS.

However, thousands of them are still practicing their religious rituals and speak their Syriac language in their churches, which are mainly spread in al-Hasakah and some Syrian areas on a smaller scale.

Assyrians title is often associated with Syriacs and this is justified by their national unity. The difference between them revolves around the religious sect. According to Syrian writer Taysir Khalaf, Syriacs are members of the Western Syriac Church and Assyrians are followers of the Eastern Syriac Church, also called Nestorian.

Assyrian politicians seek to overcome these differences by adopting the name “Syriac Assyrians.” However, some Syriacs object to this confusion, which is due to certain sectarian sensitivities.

Assyrians have largely coexisted with the other Syrian components, despite their attempts to maintain their existence and not to compromise their integrity. Some Assyrian activists believe that the Ba’ath Party pursued an “aggressive” policy with them, fighting their culture and preventing them from political activism.

Today, Assyrians are present in the political arena through some political parties, most notably the Assyrian Democratic Organization (ADO), which is affiliated with the Syrian opposition. Some of their children are also fighting within two military factions, one of which is loyal to the regime and the other is fighting next to the opposition. Some of them are relying on civil activity as a means of preserving rights and national identity.

These internal divisions in the Assyrian population reflect to a certain extent a general state of division and confusion in Syria, but pose a greater threat to the Assyrians as a religious minority threatened by the flood of war in Syria.

Between the Church and the Military: The ADO is the Most Prominent Political Representative of Syriac Assyrians

The launching of the first Kurdish party, called the Kurdistan Democratic Party, in Syria has been followed after about a month by the announcement of the first Assyrian party in the Syrian city of Qamishli, being influenced by the rise of nationalist movements in the region. This party emerged as an attempt to acquire some cultural rights and reinforce the identity of an ethnic and religious minority within a group which includes other components of the Syrian people.

According to Abdul Ahad Astifou, the representative of the ADO in the Syrian National Coalition, “the Assyrian Democratic Organization (ADO) was established in 1957 to meet the need of Syriac Assyrians in Syria for a party that reflects their national calls for the need to recognize their existence and national identity, and to consider their Syriac language and culture as national, within the framework of the unity of Syrian land and people. During an interview with Enab Baladi, Astifou pointed out that the ADO was the first political organization to appear in the Syriac Assyrians’ community, not only in Syria, but also in the countries of the Middle East.”

Despite the emergence of several Syriac Assyrian political parties in Syria and Iraq, “they did not differ from the vision and program of the ADO.”

Astifou added that since its establishment, the ADO has pursued “peaceful democratic means of action, linked its national struggle to patriotic struggle, and considered that the national demands of the Assyrians and other nationalities in Syria can only be achieved through a secular democratic system based on justice, equal citizenship and partnership between all Syrians.”

Suppression of the Ba’ath and the Search for “Moderation”

As a political party seeking democratic change, the Assyrian Democratic Organization has witnessed attempts of repression and exclusion amid the Ba’ath Socialist Party’s control over politics since the 1970s.

“Since its establishment, the Assyrian Democratic Organization has not been authorized or recognized. Only Arab nationalist parties have been recognized under the Ba’ath Party, so automatically the organization was considered to be among opposition,” said Gabriel Moushe Gawrieh, the head of the Political Bureau of the ADO, in an interview with Enab Baladi.

Gawrieh added: “We were living under a strict security system that was preoccupied with drying up politics, and we were trying to end the monopoly of one party. We have witnessed political repression and the organization’s staff has been subjected to many arrests.”

As a result of these restrictions, the organization addressed the “national democratic forces with similar visions and ideas to work with them through frameworks and alliances aimed at bringing about real democratic change leading to the construction of a modern democratic state for all Syrians,” according to the organization’s representative in the coalition, Abdul Ahad Astifou.

Astifou pointed out that “just like any political group, the organization has gone through dialogues and intellectual tensions between leftist, rightists and nationalist parties, and tried to be the centre of balance and moderation in their proposals. I think it is still maintaining this approach.”

Therefore, members of the organization distanced themselves from political life in Syria and were unable to take part in it or obtain political positions before the revolution. In contrast, the organization participated in the 2005 Damascus Declaration for National Democratic Change, which called for ending al- Assad regime.

The Opportunity of the Cautious Revolution

As a result of the severe repression the ADO has witnessed, it had to participate in the Syrian revolution in an attempt to cease this opportunity and achieve the goals for which it was founded. But, at the same time the organization sought to preserve its peaceful revolutionary approach and its central position among the various Syrian currents and parties.

The organization has been involved in opposition frameworks ranging from the National Council to the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, and has participated in several rounds of Geneva talks.

Abdul Ahad Astifou, the coordinator of the electo

Abdul Ahad Astifou

Representative of the Assyrian Democratic Organization in the Syrian National Coalition

ral commission in the delegation of the Syrian Negotiation Commission in Geneva, pointed out that this engagement is a cumulative result in view of the history of the party and its adoption of the objectives and demands of the revolution.

This strong participation in the opposition has led to a very tight security situation imposed on its members. Several of them have been arrested and others were dismissed and prevented from travelling.

The forces of the regime arrested engineer Gabriel Moushe Gawrieh, the head of the Political Bureau of the organization and member of the General Secretariat of the Damascus Declaration for two and a half years, on charges of terrorism and incitement to violence to overthrow the regime.

Despite its support of the opposition, the relationship between the organization and the self-administration, which has been imposed by the Kurdish Democratic Union Party as a de facto authority in the Upper Mesopotamia region, was not characterized by “hostility.” According to Astifou, “the organization is not a member of the self-administration, and has no representatives there. However, it maintains positive relations with many parties and figures belonging to it.”

“We consider self-administration as an embodiment of the will and approach of the parties involved in it, but does not stand for all the political expressions of the components of the Upper Mesopotamia. Honestly, this administration is open and receptive to the rights of all the components of the region, including the Syriac Assyrians, but it is based upon unilateral ideological tendencies and a tendency towards domination and monopoly by the influencing parties. This contradicts the principle of partnership and equal citizenship that we are calling for.”

It can be said that the Assyrian Organization moves cautiously in an attempt to avoid a complete break with the various political components on the Syrian arena, and is adopting an initial call for democracy and partnership.

Against “Distorted Federalism”

The official at the Assyrian Democratic Organization political bureau, Gabriel Moushe Gawrieh, said that “the federal system has multiple positive aspects, which are reflected in the experiences of developed countries such as the United States and Germany.” He pointed out that “it is a means to prevent tyranny, and enhance the distribution of power and wealth and the development of all regions.”

“This experience has been distorted in some parts of our country. Such a change needs the consensus of all the people of Syria,” he said.

In the same context, Abdul Ahad Astifou claimed: “In principle, we are not against expanded decentralization, including federalism, which provides opportunities for the distribution of power and wealth and the achievement of balanced development for all the provinces and regions of Syria, and in such a way as to stop tyranny or any attempt to divide the country or separate a part of it.”

He added: “However, we see that any form or system of government cannot be imposed by one party on the other, as it requires a consensus in a free and democratic climate among all Syrians on the nature of appropriate management systems.”

Peaceful Approach and Justified Armament

Despite the organization’s policy of peaceful struggle and non-violence, it believes that militarization at the beginning of the Syrian revolution carries understandable and justified motives.

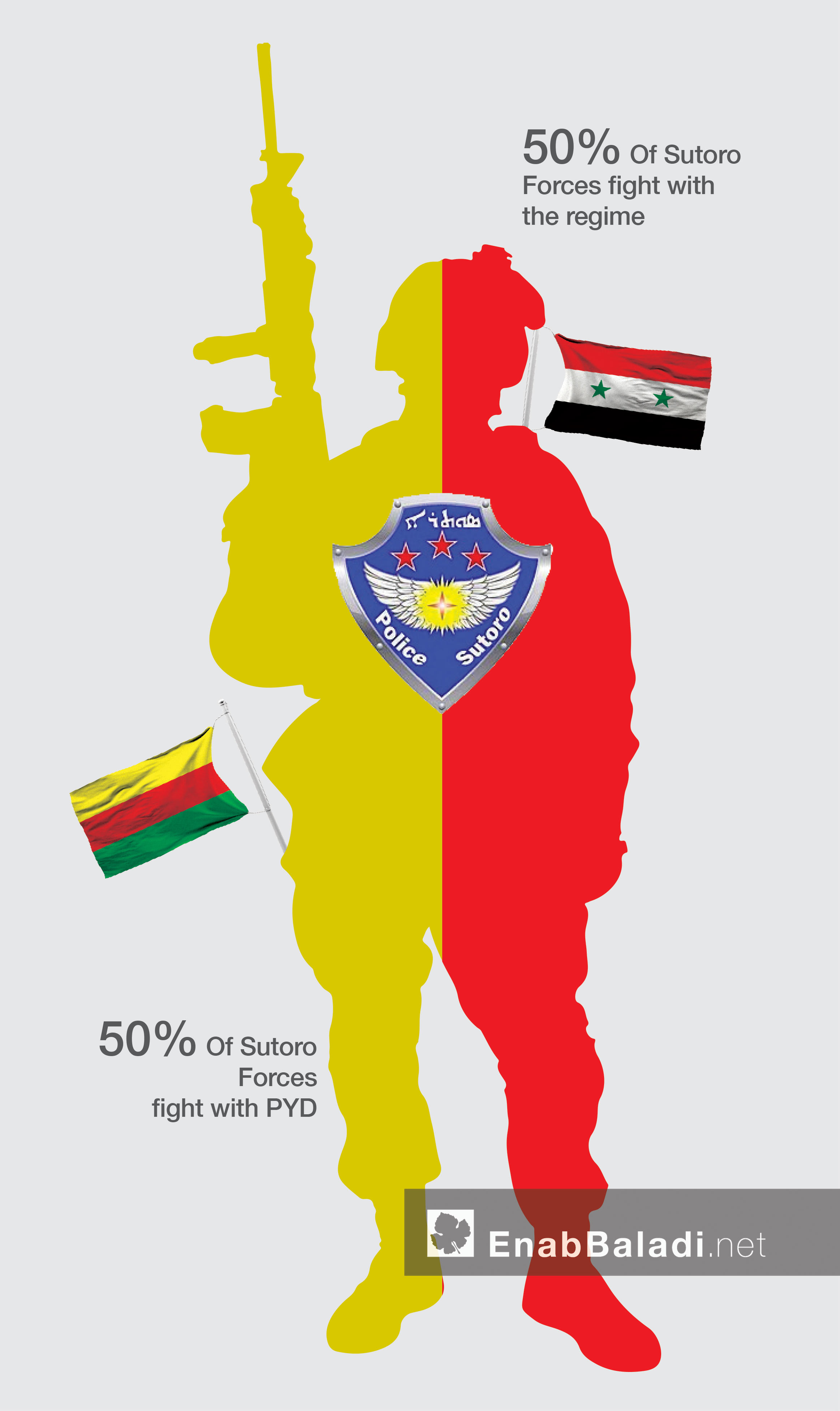

According to the same vision, the organization deals with the Syriac military wings that were formed after the revolution in the area of Mesopotamia under the name of “Sutoro” Forces, which are divided into two factions: one is affiliated with the National Defence pro-regime militias, and the other is affiliated with the “Syrian Democratic Forces” that the Kurdish fighters form its foundation.

The organization representative in the coalition, Abdul Ahad Astifou, was not surprised about the division, as it “is not limited to the Assyrians or Syriacs only, there are similar cases among the Arabs and Kurds on the island and others.”

While he described the presence of these two wings as “being symbolic more than effective, since their primary role is limited to protect the neighbourhoods and villages of our people.”

He insisted: “For us, as an organization, we adopt a peaceful and political approach in our work, and we did not think about forming an armed faction, because we were not originally for the idea of armament and militarization.”

Many Names but One Identity

Many names were attributed to the Assyrians, which often leads to confusion in understanding the relationship between these names and their association with a single national and linguistic dimension.

The representative of the Assyrian Democratic Organization in the Syrian National Coalition, Abdul Ahad Astifou, explained and referred this confusion to the “splits in the Christian Church, in its political and theological dimensions, from the early Gregorian centuries, which played the most prominent role in tearing this people into sects and communities; so it looked like labels for several people, as a result of the overwhelming influence of the religious faith and its occupation of the centre of identity in the culture of this people and the rest of the peoples of the region for long historical periods. Moreover, there was a suspicious role of Catholic and Protestant missionaries in the absence of sense of identity and culture, and the establishment of spiritual references, and then Western cultural trends that in turn contributed to deepening the division.”

This is in addition to “Ottoman politics in sustaining the “Millet” regime, which means (people) in the form and context of the community. Therefore, the labels that today are given to this people by many of its individuals are identical to the name of the church that it follows, such as Syriac, Assyrian or Chaldean,” according to Astifou.

As for the linguistic designations, he clarified: “Since the fourth century BC, all Mesopotamia and even to the shores of the Mediterranean were called Greece. They were subject to the Assyrian Empire according to the Greek word that does not contain the “Shin” letter, as ASSYRIA and its inhabitants ASSYRIAN. This new word was reinforced through the Aramaic language that was the language of the entire Assyrian Empire in (Soroyo) or (Suraya) according to the prevailing dialect in each region. The word “Syriac” has been established in the Arabic language, and many respected historians and scholars have confirmed this linguistic derivation between the Syriac and Assyrian names.

“The word Assyrian is the Syriac word for the word Othoroyo. The word Assyrian is expressed in the Syriac language as (Othoroyo or Athuraya), which is the name adopted by the founders of the Assyrian Democratic Organization,” said Astifou.

The “Sutoro” … A Military Wing between the Regime and “PYD”

After the start of the Syrian revolution in 2011 and the accompanying changes in the facts and events, military movements and formations of different names and affiliates emerged on the front, and initially took the task of protecting the areas where they were established. But later, its military activity expanded and reached the advanced stages of controlling regional countries.

| The Sutoro was declared in March 2013 and presented itself as a force to protect the Christian areas of Mesopotamia from attacks by Al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State, and it includes Assyrians and Syriacs. |

The cities of al-Hasakah and Qamishli were among the areas which witnessed the emergence of military formations. Along with al-Assad forces militias, the Kurdish “People’s Protection Units” and the “Free Army” factions that were active at that time, a military formation emerged from the Christian minority under the name “Sutoro,” which undertook the task of protecting Christian areas in Mesopotamia from the attacks committed against them.

Media sources from Qamishli told Enab Baladi that the Sutoro Forces are deployed in the cities of al-Hasakah, Qamishli, al-Malikiyah and al-Qahtaniyah, as well as 30 villages located along the Khabur River, starting from the south of Ras al-Ayn in the north up to Mount Abdulaziz in the south.

It includes young people from Syriac Christian parties such as the “Syriac Union Party” (the Dawronoye), the “Assyrian Democratic Organization, “the Syrian Youth Assembly”, and “the Christian Civil Society.”

Two Groups Having Different Tasks

The Sutoro is divided into two groups, the first of which is affiliated with the Syrian regime. Its militants are members of the Orthodox Peace Council of the Syriac Orthodox. They directly receive money from the regime. Their duties are concentrated at the checkpoints deployed in the city of Qamishli, especially al-Wusta neighbourhood, the Christian majority quarter.

The other group is affiliated with the PYD. Its militants are members of the Syriac Union Party. Its influence is concentrated in al-Malikiyah and al-Qahtaniyah north-east of Qamishli and in the city. Its militants receive their financial and military support from the Kurdish units. They are treated like the original “units” militants.

The Syrian regime Sutoro military action is not limited to the Qamishli and surrounding areas only, but part of them participated in al-Assad force’s battles in the eastern Homs countryside and the vicinity of the capital Damascus.

In November 2015, part of the forces moved to the predominantly Christian city of Sadad, east of Homs, and participated in countering the “Islamic state.”

At the time, video recordings were published showing Father Gabriel Daoud, a Christian priest, on an inspection tour of the forces east of Homs.

Sources familiar with the issue told Enab Baladi that the reasons for the affiliation of Christian youth in Qamishli to the regime Sutoro are to solve the problem of compulsory service, as they are not called to the reserve army and are not completely prosecuted.

Two Leaders for Military Command

Sarkon Chamoun commands the forces’ wing of the command regime, together with Gabriel Daoud in the supervision mission, who is originated from the city of al-Malikiyah (Derik).

Whereas the leader Malki Rabo heads the military wing of the “PYD,” and his work is mainly focused on the “Asayish” security apparatus.

According to previous media reports, the Sutoro of the Democratic Union Party has become an integral part of it and has direct contact with Kandil. It has played a prominent role in the military operations against the Islamic State, especially in the southern al-Hasakah countryside.

In addition to the support that forces receive from the regime and the PYD, researcher Asaad Hanna said in a lengthy research published last year that the forces rely on donations from businessmen and Christian business owners. The other side of the money comes from expatriate Christians in Europe.

The researcher added that the parties that are affiliated to the Sutoro have clubs and associations in European countries, especially Sweden, the Netherlands and Belgium. Some of these associations collect donations and send them to Syria to support the military and service operations that are offered by the Christian forces.

Special Military Academy for the Sutoro

In November 2014, the Sutoro established the first Assyrian (Syriac) military academy, called the Martyr Agha Boutros Academy in the Corniche area in Qamishli, and was affiliated to the military wing which receives military support from al-Assad’s forces.

At that time, international news agencies quoted Assyrian sources as saying: “The fear of the Syriac / Assyrian community of changes in the security situation in northern Syria made them form military forces and centres to defend the Christian presence in the region.”

The combatants in the academy are receiving “practical and theoretical military” trainings, and the Christian religious centres provide them with lectures and doctrinal guidance.

Syrian human rights organizations accused the regime of “trading” and targeting Christians between 2014 and 2015, confirmed that the regime have killed more than 100 Christian people, and accused it of seeking to “exploit minorities, especially Christians” since the beginning of the revolution.

The Assyrian Civil Movement in al-Hasakah

The civil movement of the Assyrians in al-Hasakah have developed during the last few years, as it has been the case with other society components. After the absence of the civil society activity in the past, it has started to develop since the beginning of 2012 in all Syrian regions.

| “Eridu Centre for Civil Society and Democracy was established in May 2013. It has sponsored several activities in Qamishli in al-Hasakah, and defines itself as an independent, non-profit social organization that is aimed at supporting and spreading the culture of civil society within the various segments of Syrian society.”

|

The civil work of the Assyrians is currently limited to a number of associations and centres, on top of which are Eridu Centre for Civil Society and Democracy and Ashur Foundation for Relief and Development.

Enab Baladi has interviewed Ghandi Saado, Executive Director of Eridu Centre in Qamishli, who said that this centre’s activities focus on three axes: raising awareness about the basics of civil society, developing youth skills and abilities, governance and institutions.

The Centre’s most prominent activities include four festivals in the name of “Spring,” and campaigns, most notably “Do Not Be a Wound,” against racial discrimination. According to its executive director, it does not only target the Assyrians, but also Arabs, Kurds, Syriac and Armenians, regardless of national and religious affiliation.

The Centre is seeking to achieve equality among all, “which would ensure that all the society segments would have the opportunity to express themselves, in accordance with their cultural, national and religious vision,” according to Saado.

Some of the Centre’s principles are the consolidation of the concepts of civil peace and coexistence and the introduction of civil ideas into society, according to the Executive Director. He pointed out that achieving these principles “is carried out through training workshops for some young people, media campaigns or cultural activities.”

Saado believes that civil work is important for the preservation of the cultural identity. He clarified that the Assyrians and Syrians as a whole were absent from this sector, as there were no real and effective civil institutions on the ground in the past. He added that “Assyrians in particular have been subjected to Arabization campaigns in the region at both geographical and cultural levels, because of the behaviour of Ba’ath Party and the ruling authority in Syria.”

From Saado’s point of view, reviving the cultural specification “is important, but with the recognition of other cultures as we live in a diverse society.” He pointed out to the need to “correctly and properly express ourselves.”

The Centre’s Executive Director considered that the situation of civil action in al-Hasakah is still at low levels within the province that cannot be assessed, but it would be unfair because it has not yet exceeded five years and they are not enough to evaluate it.” He stressed that the civil action is growing and developing, and added that “there are a lot of institutions which are standing out and others are still learning and developing.”

The Executive Director of Eridu Centre explained why Assyrian organizations have not been active in civil action, saying that the Syrian society in general “has not been effective at both civil and political levels. This is not limited to the Assyrians, as few other society segments were involved in political and civil action in a simple way.”

After the revolution, Syria has become open to political diversity and wider civil movement. Assyrian society has been always absent, and this has hindered the large and clear output within a short period of time, as Saado put it.

According to Saado, the Centre and civil organizations in Al-Hasakah need learning and training at a greater level, to raise awareness and expertise in the civil field, and to stand against constraints and conditions that restrict the work such as the lack of financial support, customs and traditions.

Eridu Centre is continuously seeking to develop the structure. It includes a general secretariat, a board of directors and offices, while the number of its members changes depending on volunteerism. There is an estimated number of between 20 and 25 employees at two centres in Qamishli and al-Malikiyah.

Syriac Churches that have been Destroyed in Syria

Many Syriac churches are nowadays spread in different areas of Syria, some of which are archaeological, and some date back to less than a century.

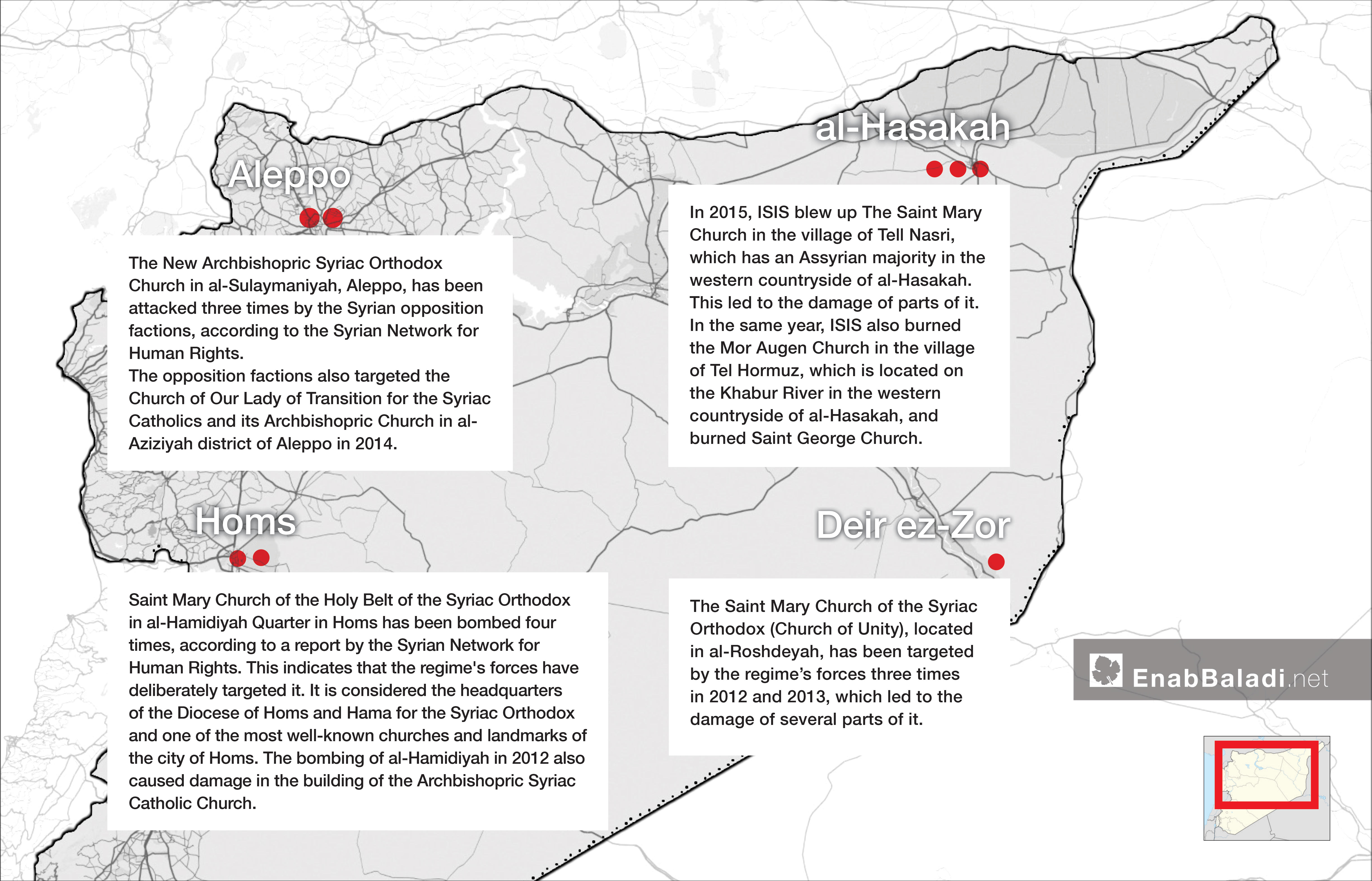

A number of these churches have been either partially or totally destroyed following the war in Syria. On the Syrian island and Raqqa, ISIS has targeted the Christian minority and intentionally destroyed or ruined some churches. The Syrian regime has targeted churches in Homs, Aleppo, Daraa and Deir ez-Zor.

According to a report which was issued by the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) in 2015, the Syrian regime is responsible for the destruction of 63% of the total number of churches throughout Syria.

Since then, other churches have been destroyed or ruined either by ISIS, al-Nusra Front, or by the raids of the International Coalition.

Homs

Saint Mary Church of the Holy Belt of the Syriac Orthodox in al-Hamidiyah Quarter in Homs has been bombed four times, according to a report by the Syrian Network for Human Rights. This indicates that the regime’s forces have deliberately targeted it. It is considered the headquarters of the Diocese of Homs and Hama for the Syriac Orthodox and one of the most well-known churches and landmarks of the city of Homs.

The bombing of al-Hamidiyah in 2012 also caused damage in the building of the Archbishopric Syriac Catholic Church.

Deir ez-Zor

The Saint Mary Church of the Syriac Orthodox (Church of Unity), located in al-Roshdeyah, has been targeted by the regime’s forces three times in 2012 and 2013, which led to the damage of several parts of it.

Aleppo

The New Archbishopric Syriac Orthodox Church in al-Sulaymaniyah, Aleppo, has been attacked three times by the Syrian opposition factions, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

The opposition factions also targeted the Church of Our Lady of Transition for the Syriac Catholics and its Archbishopric Church in al-Aziziyah district of Aleppo in 2014.

Qamishli

In 2015, ISIS blew up The Saint Mary Church in the village of Tell Nasri, which has an Assyrian majority in the western countryside of al-Hasakah. This led to the damage of parts of it.

In the same year, ISIS also burned the Mor Augen Church in the village of Tel Hormuz, which is located on the Khabur River in the western countryside of al-Hasakah, and burned Saint George Church.

if you think the article contain wrong information or you have additional details Send Correction

النسخة العربية من المقال

-

Follow us :

Assyrians celebrating Easter in Tal Arboush in Northern Syria – April 1. 2018 (AFP)

Assyrians celebrating Easter in Tal Arboush in Northern Syria – April 1. 2018 (AFP)

A

A

A

A

A

A

More In-Depth

More In-Depth